(This post is based on episode 11 of the Review the Future Podcast. For a more detailed treatment of this topic you can subscribe to the podcast via iTunes or download it from reviewthefuture.com.)

What is this Book?

What is this Book?

The Second Machine Age is a book by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee that explores the impacts of new technologies on the economy. For those who are familiar with such topics, it’s not likely this book will teach you much you don’t already know. However, for the layperson, this book is an extremely well written and clear introduction to the economic pros and cons of our current digital revolution. Because of the skillful way it stitches everything together, Second Machine Age has a good chance of being one of the most important nonfiction books of 2014.

The Goal of this Blog Post

On the whole, we like The Second Machine Age. We think it tells a plausible story and for the most part we agree with its perspective. However, we have criticisms of one of the book’s later chapters, the one entitled “Long-Term Recommendations.” Thus the primary goal of this article is to articulate those criticisms. But first, for the sake of background, we will summarize some of the book’s main arguments.

A Quick Summary of Second Machine Age

According to Brynjolfsson and McAfee, exponential gains in computing, digitization of goods, and recombinant innovation are all driving rapid technological growth. Technology has begun to perform advanced mental tasks—like driving cars and understanding human speech—that were previously thought impossible. And in economic terms, these new technologies, according to the authors, are increasing both the ‘bounty’ and the ‘spread.’

Bounty is a blanket term for all of the productivity and quality of life gains provided by new technologies. Brynjolfsson and McAfee feel that the bounty of technology is growing tremendously, but, because of the limitations of our economic measures, we have a tendency to greatly underestimate the progress we are making.

Spread is a euphemism for inequality. According to the authors, technology is increasing spread because of (a) skill biased technical change, (b) capital’s increasing market share relative to labor, and (c) superstar economics. All three of these trends have some evidence backing them up, and the supposition that technology is the primary driver of these trends makes a great deal of sense.

The authors also suggest that technological unemployment—a phenomenon long thought of as impossible by mainstream economists—is in fact possible. They discuss three arguments for how technological unemployment could occur:

- In industries subject to inelastic demand, automation can lower the price of goods without creating any additional demand for those goods (and thus labor to make those goods). Over the long term, as human needs become relatively more satiated, this inelasticity could even apply to the economy as a whole. Such an outcome would directly undermine the luddite fallacy, which is the argument economists traditionally use to dismiss technological unemployment.

- If technological change is fast enough, it could outpace the speed at which workers are able to retrain and find new jobs, thereby turning short term frictional unemployment into long term structural unemployment.

- There is a floor on how low wages can go. If automation technology continues to drive wages down, those wages could cross a threshold below which the arrangement is not worth the employee’s time. Eventually the value of certain workers could fall so low that they are not worth hiring, even at zero price.

Policy Recommendations

The book makes several short term policy recommendations. We will not list them all here, as they represent a suite of largely uncontroversial proposals designed to speed up innovation and growth. These proposals, if they were enacted, would conceivably help to get our economy working more efficiently and increase our ability to match workers to the jobs that still need doing. They would also grow the technological bounty that makes all of our lives better. It’s hard not to agree with most of these proposals.

However, if we accept the premise that “thinking” machines will encroach further and further into the domain of human skills, and that over the long term we are destined for not just rampant inequality but also wide scale technological unemployment, then all of the short term proposals provided by this book could actually accelerate unemployment. After all, more innovation means more and better machines, which ultimately could mean more displaced labor.

Long Term Recommendations

In this chapter, the authors address long-term concerns. In a near future where androids potentially substitute for most human labor, will the standard economics playbook still work?

Brynjolfsson and McAfee are clear about two major preferences:

- They do not want to slow or halt technological progress.

- They do not want to turn away from capitalism, by which they mean, “a decentralized economic system of production and exchange in which most of the means of production are in private hands (as opposed to belonging to the government), where most exchange is voluntary (no one can force you to sign a contract against your will), and where most goods have prices that vary based on relative supply and demand instead of being fixed by a central authority.”

We agree with these two premises. So far, so good.

Should we Adopt a Basic Income?

The authors go on to discuss an old idea: the basic income. This is a potential solution to the failure mode of capitalism known as technological unemployment. If an increasingly large number of people can longer find gainful employment, then the simplest solution might be to just pay everyone a basic income. This income would be given out to everyone in the country regardless of their circumstances. Thus it would be universal and unconditional. Such a basic income would ensure that everyone has a minimum standard of living. People would still be free to pursue additional income in the marketplace, and capitalism would proceed as usual.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee do a quick survey of all of the varied thinkers, both conservative and liberal, who have supported this idea in the past. Here’s a short list of people who favored a basic income:

Thomas Paine, Bertrand Russell, Martin Luther King Jr., James Tobin, Paul Samuelson, John Kenneth Galbraith, Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, Richard Nixon

With such wide ranging endorsement for the idea of a basic income, one might expect Brynjolfsson and McAfee to jump on the bandwagon and endorse the idea themselves.

But, no! Basic income is apparently “not their first choice.” Why?

Because work, they argue, is fundamentally important to the mental wellbeing of people. If we adopted a basic income, people might not be adequately incentivized to work. And therefore people and society would suffer on some deep psychological level.

To support this idea, Brynjolfsson and McAfee field a series of arguments.

Argument One: A Quote From Voltaire

The french enlightenment philosopher Voltaire once said, “Work saves a man from three great evils: boredom, vice, and need.” Now, Voltaire was a pretty smart guy, but whether someone from the eighteenth century has anything helpful to say about today’s technological reality seems doubtful. But for the sake of argument, let’s go ahead and examine this quote.

First of all, we’re not sure what Voltaire meant by “work.” Work can mean a lot of things. Work, in the broadest sense, could mean activities you do to upkeep your life, such as cleaning your bathroom or going grocery shopping. It could also consist of amateur hobbies that you undertake for fun, such as writing overly long blog posts.

However, this is not the definition of work that Brynjolfsson and McAfee are implying. They are implying a much more narrow definition of work as ‘wage labor’—meaning work done to serve the needs of the marketplace. Wage labor is work you do, at least in part, to earn money, so that you can continue to survive and exist in this modern world.

So let’s rephrase the quote to: “Wage labor saves a man from three great evils: boredom, vice, and need.”

Already this should start to sound a little bankrupt. Wage labor saves a man from boredom? Sure, a good job can relieve boredom. But a bad job can be one of the single biggest causes of boredom in a person’s life. We don’t have any statistics on this, but anecdotally we happen to know a lot of people who don’t particularly enjoy their jobs. And boredom is one of the biggest complaints these people have. A quick survey of the popular culture surrounding work would seem to imply that this is not a unique sentiment. We have a feeling that you, the reader—if you try hard enough—can think of at least one person who gets bored at their job.

(ADDITION: Gallup Poll Shows Thirteen Percent of Workers are Disengaged at Work)

So what about ‘vice?’ What even constitutes vice in 2014? Things you do for pleasure that are bad for you? Honestly, the word vice seems a bit anachronistic in this day and age, but we can think of some candidates for vice that are actually encouraged by wage labor:

- Aimless web browsing and perusing of “trash” media to ease the boredom of being stuck in a cubicle

- Sitting in a chair all day not exercising and slowly harming your health

- Drinking copious amounts of soda and coffee in order to stay awake during the hours demanded by your job

- Cooking less and eating more junk food because wage labor takes up too much of your time

- Needing a drink the second you get home in order to unwind after a stressful day of wage labor

Third on Voltaire’s list is ‘need’. But if wage labor could take care of need, we wouldn’t be having this conversation in the first place, right? Since we are speculating about a future where automation makes most work obsolete, then it is clear that in such a future most people will not be able to find lucrative wage labor. So looking ahead, wage labor cannot necessarily save a man from need any more than it can save a man from boredom or vice.

Argument Two: Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose

Brynjolfsson and McAfee attempt to use Daniel Pink’s book Drive to further their point. Drive discusses three key motivations—autonomy, mastery and purpose—that improve performance on creative tasks. However, the authors of Second Machine Age seem to imply that (1) these qualities are needed for psychological wellbeing and (2) these qualities can best be obtained from wage labor. This is a misapplication of Drive’s actual thesis.

The three motivations described—autonomy, mastery and purpose—are not fundamental qualities of wage labor. In fact, wage labor is historically very bad at providing them. Thus, Pink’s book explains how modern businesses can specially incorporate these techniques in order to try to get better results from their workers.

Such mind hacking aside, wage labor has no special claims to autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Wage labor removes autonomy by forcing people to focus their energies on what the market thinks is important, rather than on what they themselves think is important. Mastery can just as easily be found in education, games, and hobbies. And purpose can be found in religion, philosophy, community service, family, country, your favorite sports team, or really just about anywhere.

Argument Three: Work is Tied to Self-Worth

The authors cite the work of economist Andrew Oswald who found “that joblessness lasting six months or longer harms feelings of well-being and other measures of mental health about as much as the death of a spouse, and that little of this decline is due to the loss of income; instead, it arises from a loss of self-worth.”

We don’t doubt that a loss of self-worth is a major factor contributing to the unhappiness of the long-term unemployed. However, we believe this outcome is culturally and not psychologically determined. The cultural expectations in America are that you are supposed to get a wage labor job and earn your living every day, otherwise you are seen as a freeloader, a layabout, a good-for-nothing. Jobs are seen as the premiere source of personal identity, and the first question out of most people’s mouths when they meet someone new is “what do you do?” We don’t see why these cultural expectations can’t change and in fact, if the premise of technological unemployment is correct, then they will have to change.

Laziness and doing nothing may always be looked down upon. But there is a big difference between doing nothing and being unemployed. As has already been articulated, there are many productive ways to spend one’s time that have nothing to do with wage labor. If our society fails to recognize the value of these non-wage labor pursuits, then the problem lies with society.

Today unemployment may be higher than we like, but work is still abundant enough that such a cultural expectation can remain unchallenged. But if the future looks like the one implied by Second Machine Age—a future where more and more people will be unable to find wage labor—then long-term unemployment will need to become not just normalized, but accepted. By reaffirming the importance of wage labor, Brynjolfsson and McAfee are helping to perpetuate the same social force that already makes unemployed people feel depressed and worthless.

Argument Four: Without Work Everything Goes Wrong

The authors cite studies by sociologist William Julius Wilson and social research Charles Murray that suggest unemployed people have higher proclivities towards crime, less successful marriages, and other problems that go beyond just low income.

Unlike Drive, we have not personally looked at this research so we cannot speak directly to the experimental rigor of these studies. Isolating for the effect of joblessness in real world communities is extremely difficult and requires controlling for a wide variety of complicating factors. In the case of Murray’s work, the authors seem to acknowledge this concern directly when they write “the disappearance of work was not the only force driving [the two communities] apart —Murray himself focuses on other factors—but we believe it is a very important one.”

As long as wage labor is directly tied to income, how can we be sure that what these studies are actually measuring is not “incomelessness?” In order to sidestep this issue, we would maybe like to see a study of two groups—one that receives a comfortable income without working, and one that receives an equivalent amount of money, but must work for it. What differences would exist between these two groups? Would the non-working group become aimless and depressed? Or would they simply repurpose their free time towards other productive tasks?

Negative Income Tax

After all this discussion of the fundamental importance of wage labor, one might expect Brynjolfsson and McAfee to recommend the creation of a Works Progress Administration or some other mechanism for artificially creating jobs. Instead they just double back and return to the basic income idea, only by another name.

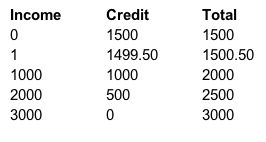

The authors support Milton Friedman’s idea of a negative income tax. They claim that a negative income tax better incentivizes work. However, this distinction between a basic income and a negative income tax does not actually exist. Both a basic income and a negative income tax have two key features in common: they set an income floor below which people cannot fall, and at the same time they allow people to increase their relative income through labor. Thus we see no basis for the notion that a negative income tax better incentivizes work.

After doing some light research into Milton Friedman’s original statements we realized one possible source of the confusion. In this video, Friedman articulates the argument that a negative income tax will do a better job of incentivizing work than a “gap-filling” version of the basic income. This is certainly true. A gap-filling basic income would probably be a bad idea and have the problem of disincentivizing labor below a certain threshold. However, to our knowledge, none of the modern day basic income proposals are built around this gap-filling principle, so Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s distinction seen in this light would be a bit of a straw man argument.

What are the Goals?

We should not forget that wage labor is not the goal in itself. The real goals of our economy ought to be (1) alleviate people’s suffering and (2) increase the bounty through innovation. Although there are challenges involved, a basic income would seem to be a promising way to address both of these goals.

A basic income puts a floor on poverty and does so in a way that is both much simpler than our current alphabet soup of social programs, and more encouraging of autonomy. Rather than providing people with prescribed social services, people could spend their basic income dollars on whatever they feel they need. A basic income decentralizes decision making and puts the power in the hands of individuals.

As a corollary, a basic income might help unlock innovation by bringing people up to the subsistence level and thereby ensuring that they have the opportunity to compete and innovate in the market economy. Moreover, the safety net of basic income might spur entrepreneurship by reducing the risk of starting a small business. Is it possible more people would attempt to start businesses if they knew they had a cushion of basic income to protect them in the event of failure? (And as we all know, most new businesses have a high chance of failure.)

Under a basic income, there is no doubt that some people would choose to forgo wage labor altogether and live at the poverty line. But is this such a bad thing? These people would be making a personal choice. And we imagine many such people would find interesting and productive ways of spending their time that might be culturally valuable, even if they do not carry a price in the marketplace. If a musician chooses to live off of a basic income and make music, he doesn’t make money in the economy, but we all still get to enjoy his music. If a free software programmer chooses to live off a basic income, he doesn’t make money in the economy, but we all still get to enjoy his free software. If a history enthusiast chooses to live off a basic income, he doesn’t make money in the economy, but we all still get to enjoy his Wikipedia articles. As Brynjolfsson and McAfee argue earlier in the book, the value generated by digital content is not always well measured or compensated by the marketplace, but that doesn’t mean such content doesn’t improve our lives.

However, we may be preaching to the choir since Brynjolfsson and McAfee, despite their protestations, do in fact support a basic income. They just prefer the particular version of basic income that goes by the name “negative income tax.”

Pause for Skepticism

Now, it is worth noting that the “end of work” scenario is not a foregone conclusion. Here are two potential defeaters to this outcome:

- Human capabilities are not necessarily fixed. One byproduct of future technologies might be a redefinition of what it is to be human. If we begin to “upgrade” humans, whether through genetics or brain-computer interfaces or some other means, many technological unemployment concerns could become irrelevant. Upgradeable humans could solve both the retraining problem (just download a new skill set to your brain, matrix-style) and the issue of inelastic demand (super-humans might develop brand new classes of needs).

- A wide range of intangible goods—such as attention, experiences, potential, belonging, and status—might remain scarce indefinitely and continue to drive a market for human labor, even after the androids have arrived. Although it’s hard to imagine a market in such goods replacing our current manufacturing and service economy, it must have been equally hard for pre-industrial people working on farms to imagine the economy of today. Thus we may simply be lacking imagination when it comes to envisioning the jobs of the future. (For a more detailed discussion of this topic see episode 10 of the Review the Future podcast.)

Despite these defeaters, we definitely think the technological unemployment scenario is worth thinking about. First of all, the issue of timing is paramount, and at present it seems like we have a good chance of automating away many jobs long before we figure out how to upgrade human minds or develop brand new uses for human labor. Second, it won’t take anything close to full unemployment to create problems for our system. Even a twenty percent unemployment rate, (or an equivalent drop in Labor Force Participation) for example, might be enough to trigger a consumer collapse or at least great suffering and social unrest among lower classes.

Final Thought

Wage labor is a means to an end, not an end in itself. While the Second Machine Age paints a clear picture of some of the potential problems facing our economy, it fails to fully take to heart this fundamental distinction.

This is Economics 101. For a good to have a price on the market, it must be scarce. That is, the good must be in demand and exist in limited supply. If you have only one of these two elements, the good will not be worth anything.

This is Economics 101. For a good to have a price on the market, it must be scarce. That is, the good must be in demand and exist in limited supply. If you have only one of these two elements, the good will not be worth anything.

It should be acknowledged that abundance in one area often gives rise to new scarcities in another. An abundance of fatty foods gives rise to a scarcity of healthy choices. An abundance of entertainment options gives rise to a scarcity of time to enjoy them all.

It should be acknowledged that abundance in one area often gives rise to new scarcities in another. An abundance of fatty foods gives rise to a scarcity of healthy choices. An abundance of entertainment options gives rise to a scarcity of time to enjoy them all. Inequality arises from the fact that the few remaining scarce resources are increasingly concentrated in the hands of the few. We can think of the economy as like a game of musical chairs where the chairs are scarce resources. As the chairs get removed, fewer and fewer people have a place to sit.

Inequality arises from the fact that the few remaining scarce resources are increasingly concentrated in the hands of the few. We can think of the economy as like a game of musical chairs where the chairs are scarce resources. As the chairs get removed, fewer and fewer people have a place to sit. If technological progress is undermining our market system, one option is to try to stop technological progress. This could take the form of government bans on automation technologies that displace human workers.

If technological progress is undermining our market system, one option is to try to stop technological progress. This could take the form of government bans on automation technologies that displace human workers.

Specifically, I favor new platforms if they can be made to work. Barring that, I would vastly prefer to move in the direction of expanded welfare rather than artificial scarcity. My intuition is that scarce resources are best handled by markets, care of people is best left to governments, and abundance is best left unfettered by artificial scarcity.

Specifically, I favor new platforms if they can be made to work. Barring that, I would vastly prefer to move in the direction of expanded welfare rather than artificial scarcity. My intuition is that scarce resources are best handled by markets, care of people is best left to governments, and abundance is best left unfettered by artificial scarcity. Most solutions to societal problems fall into one of three categories—cultural, legal, or technological. Consider a disabled man, who lacks the use of his legs. We want to ensure that this man has equal access and isn’t unfairly discriminated against. We can institute:

Most solutions to societal problems fall into one of three categories—cultural, legal, or technological. Consider a disabled man, who lacks the use of his legs. We want to ensure that this man has equal access and isn’t unfairly discriminated against. We can institute: This might seem like an obvious point I’m making, but I find that all too often people tend to inadvertently leave technological solutions out of debates. Many arguments get bogged down in fights between two competing legal solutions. Meanwhile some lateral technological solution is just sitting there, waiting to be exploited. Often times, the energy that is spent fighting over competing policy visions, could be better spent fostering some engineering project. For example, what would save more lives per unit of effort? Fighting a difficult political battle to enact tougher gun control laws aimed at criminals who are already set on breaking the law? Or researching

This might seem like an obvious point I’m making, but I find that all too often people tend to inadvertently leave technological solutions out of debates. Many arguments get bogged down in fights between two competing legal solutions. Meanwhile some lateral technological solution is just sitting there, waiting to be exploited. Often times, the energy that is spent fighting over competing policy visions, could be better spent fostering some engineering project. For example, what would save more lives per unit of effort? Fighting a difficult political battle to enact tougher gun control laws aimed at criminals who are already set on breaking the law? Or researching